Fantastic Futures 2025

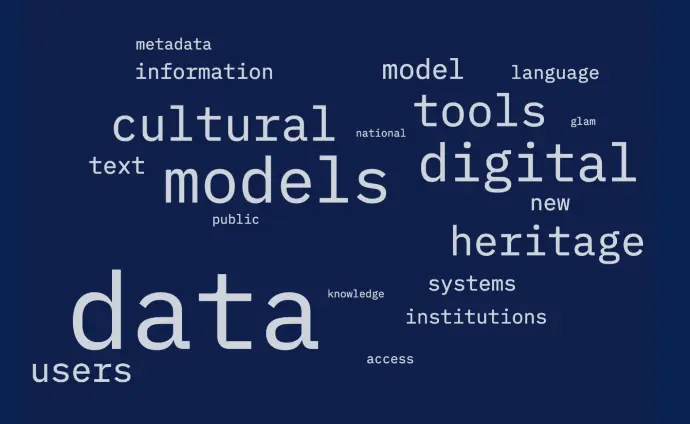

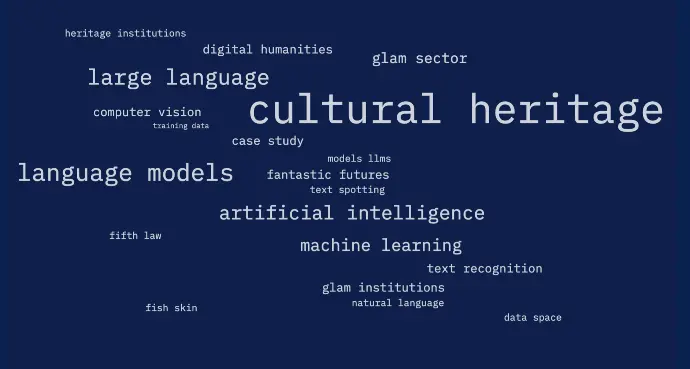

Fantastic Futures is the annual conference of AI4LAM (AI for libraries, archives, museums), where leading professionals explore how artificial intelligence and machine learning can serve heritage collections.

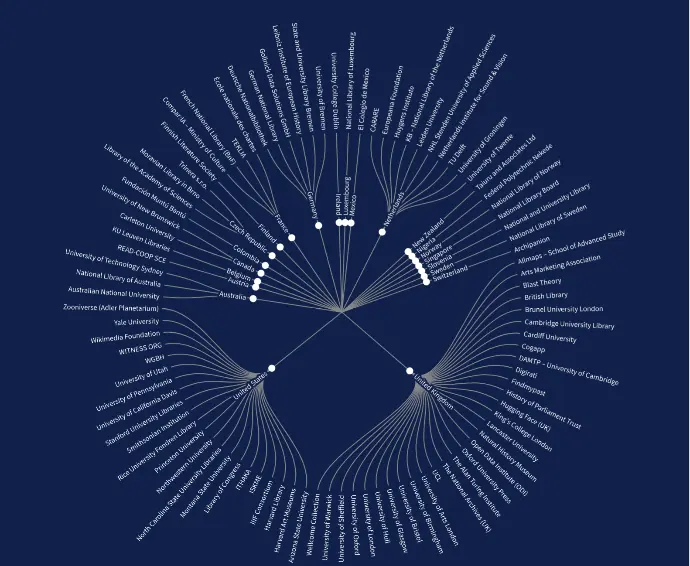

AI projects in libraries,archives and museums around the world

The following infographic looks at Fantastic Futures participants to map innovative AI projects in the sector. Most of the participants were academics from Western universities, with library professionals coming second. Museums, archives and governmental institutions are still under-represented.

Short Paper: Errare Machina Est

Christopher Kermorvant presented his short paper "Errare Machina Est?" on December 5th at the British Library in London. His presentation used as a case study the SocFace project, for which TEKLIA processed a hundred year of French national census.

Errare Machina Est?

Christopher Kermorvant - TEKLIA

Lionel Kesztenbaum - Paris School of Economics, France

Introduction

Automatic information extraction using artificial intelligence—particularly handwritten text recognition (HTR)—is transforming research in the quantitative humanities [1]. By automating the transcription of vast archival collections, AI enables the creation of datasets of a scale previously unimaginable. The SocFace project exemplifies this shift: it aims to process all surviving French census records from 1836 to 1936, covering more than 25 million pages and an estimated 500 million individual entries. Using an AI pipeline for page classification, text recognition, and entity tagging [2], we have already extracted over 150 million person-level mentions.

Yet this transformation comes with new challenges. AI-generated data are not only noisy—they are noisy in fundamentally different ways than human transcription. Errors are dispersed across a “long tail” of rare variants, and may appear deceptively accurate. This paper takes a critical look at the nature of these errors and their impact on downstream use. We ask: What types of errors do machine learning systems produce? How do they differ from human mistakes? What are the implications for research, archival practice, and genealogy? And how can we evaluate and manage them responsibly? Above all, we argue that errors are not absolute: their impact depends both on the context in which they occur and the purpose for which the data are used.

Uncertainty by Design: why AI gets it wrong

Understanding why AI makes errors starts with understanding its statistical nature. Unlike deterministic systems, AI models are probabilistic, predicting outcomes based on patterns in training data rather than fixed rules. The accuracy of these predictions depends on the quality of the input, the structure of the document, and how well the training data represent the variation in the sources. Variability in output is not an anomaly — it's inherent to the system.

Evaluating probabilistic systems is equally complex. Although widely used, Character Error Rate (CER) often fails to convey the real impact of errors, particularly when a single character significantly alters meaning, as in names or occupations that differ by gender. Although closer to human perception, Word Error Rate (WER) also misrepresents error severity when some words carry more weight than others. In both cases, context is important: minor errors in fields with high variability can be misleading, whereas major errors in more constrained fields are easier to detect. Metrics such as precision and recall provide a more targeted evaluation, but they require adaptation to noisy environments such as fuzzy searches.

Too wrong to read, or too polished to be true?

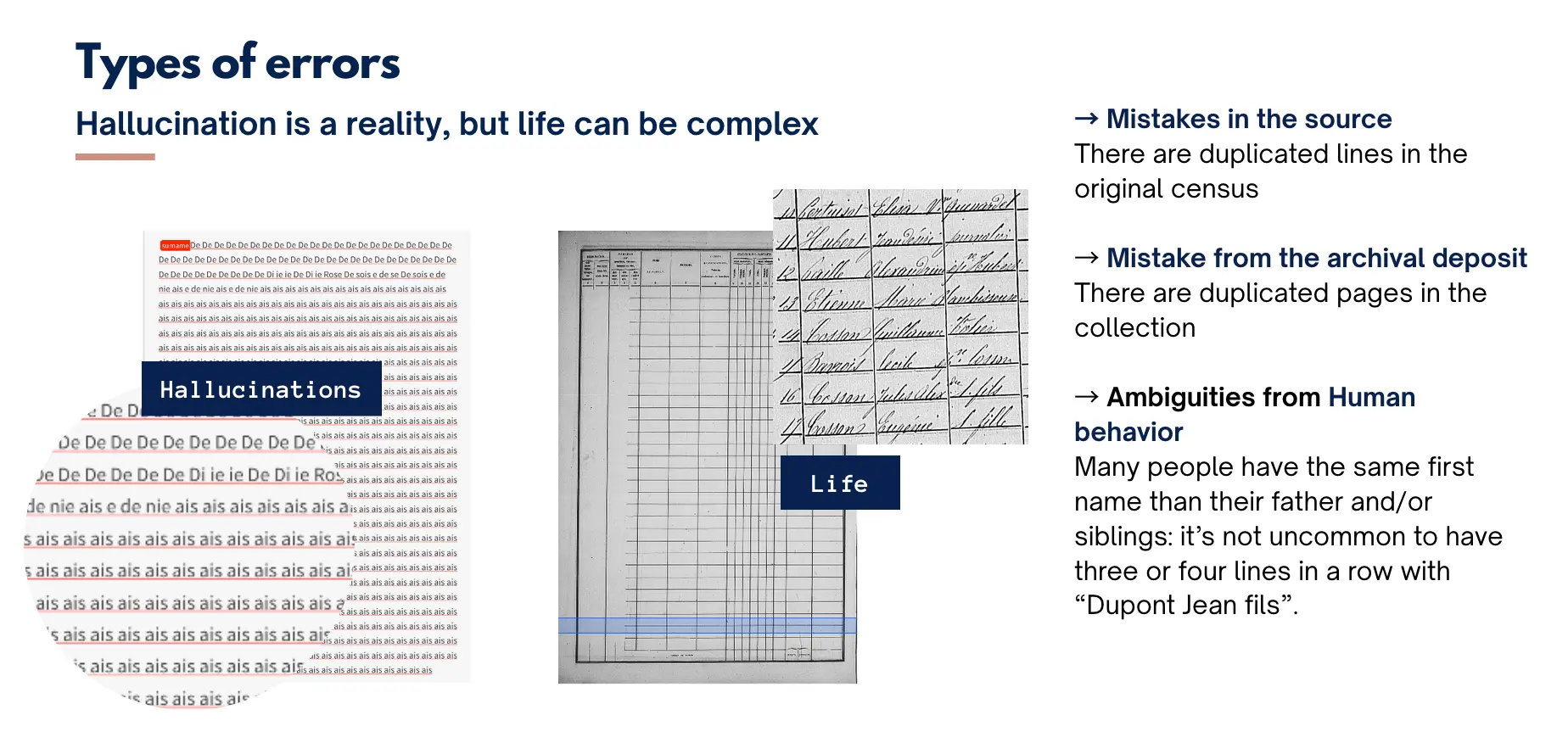

Errors produced by AI systems generally fall into two broad, equally problematic categories. The first category includes non-words or out-of-vocabulary terms — character sequences that do not correspond to any word or term in reference lists. While these errors are often easy to detect, they can be difficult to correct. Although helpful, reference lists are inevitably incomplete, and attempts at normalisation risk introducing further errors or erasing meaningful historical variation through excessive standardisation.

The second category is more insidious: hallucinations. These are grammatically and visually plausible outputs that do not correspond to anything in the original document. Unlike non-words, hallucinations cannot be identified by comparing them with external references because they blend seamlessly into the transcription. Their plausibility makes them particularly dangerous as they hinder data validation and can erode user trust in both the dataset and AI tools more broadly.

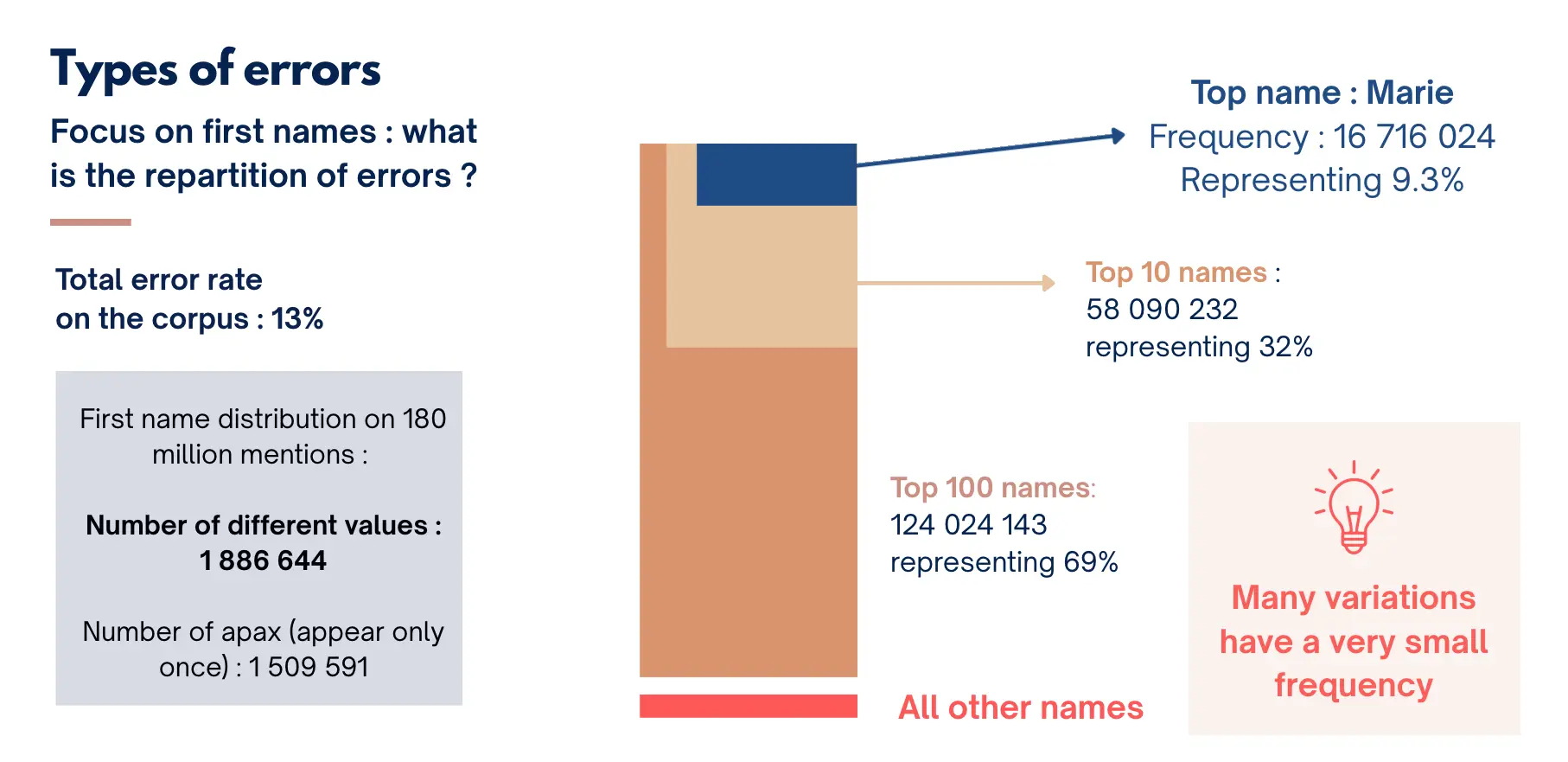

Fifty shades of wrong

Unlike humans, who tend to make a limited number of systematic transcription errors, statistical models produce a wide range of variations around the correct form. This diversity results in an 'error cloud', whereby the same name can be misrecognised in a dozen different ways, none of which occur frequently enough to be corrected systematically. We present a case study of first names in the SocFace dataset and demonstrate that the number of different first names produced by the AI model exceeds those found in reference lists and genealogical data produced by humans. This suggests that AI systems do not simply misread words, but generate a variety of approximate alternatives, some of which are closer to the correct form than others. And a huge number of them are unique occurrences, making corrections from a fixed list, whether preexisting or from a dictionary constructed from the data, very difficult. Hence, in our first batch of data containing around 140M lines from the French censuses, there are 2M different first names, among whom 1.5M are unique, many being orthographic variations that could not be produced by a human coder. These variations have direct negative impacts on linking individuals between censuses, as have been shown in the US case, with human errors [3].

This variability poses significant challenges for subsequent use. In search interfaces, for example, it undermines exact string matching and complicates fuzzy searches. In statistical analysis, it introduces data sparsity and impairs the construction of reliable aggregates. In historical inference, it can obscure or distort patterns relating to naming, migration, or family structure. The problem is not only that errors exist, but also that they are too diverse to be easily managed.

Eyes to See, Minds to Know

Due to the nature of AI-generated data, human knowledge of context, logic and domain-specific rules is crucial for identifying errors that the models themselves cannot detect. In the SocFace project, we observed that certain external features were correlated with higher error rates. For example, the final pages of registers often contained more 'hallucinations', likely due to an irregular layout or the model's assumption that every page should contain 30 lines. While these predictable patterns cannot be fully corrected, they can be flagged algorithmically.

Internal coherence checks also play a critical role. In structured records such as censuses, inconsistencies between fields — such as a daughter being older than her mother or two household heads — can indicate errors. While these contradictions may not yield automatic corrections, they offer useful clues for review and analysis.

To support end users, we advocate the creation of quality indices that combine error signals, confidence scores and contextual logic. Rather than classifying data as simply right or wrong, these indices would convey degrees of reliability to help users judge how to interpret, verify or exclude certain records.

Conclusions

Automatic transcription should not be viewed as a perfect representation of documents, but rather as a noisy gateway to historical information. Just as experimental sciences routinely deal with measurement error and uncertainty, and the social sciences have long worked with incomplete or biased datasets, scholars using AI-generated data must accept a certain degree of imperfection. The aim is not to eliminate error — an impossible task given the inaccessibility of historical truth — but rather to model and manage it.

In this context, AI transcription is not a substitute for human understanding, but rather a tool that enables access on a large scale, facilitating the analysis of vast archives that would otherwise remain inaccessible. However, this access comes with responsibilities: we must understand the sources of noise and recognise the forms that errors take. We must also build methods that account for their presence in the production of historical knowledge. In the SocFace project, we are learning to strike a balance between accuracy and scale, and between automation and expertise. The challenge is not to silence the machine's mistakes, but to learn to read through them with eyes open and minds alert.

[1] Nockels, J., Gooding, P., & Terras, M. (2024). The implications of handwritten text recognition for accessing the past at scale. Journal of Documentation, 80(7), 148-167.

[2] Boillet, M., Tarride, S., Schneider, Y., Abadie, B., Kesztenbaum, L. & Kermorvant, C.(2024). The Socface Project: Large-Scale Collection, Processing, and Analysis of a Century of French Censuses. In Document Analysis and Recognition. LNCS, vol 14806.

[3] Hwang, Sam Il Myoung, and Munir Squires (2024). Linked Samples and Measurement Error in Historical US Census Data. Explorations in Economic History 93 (July):101579.